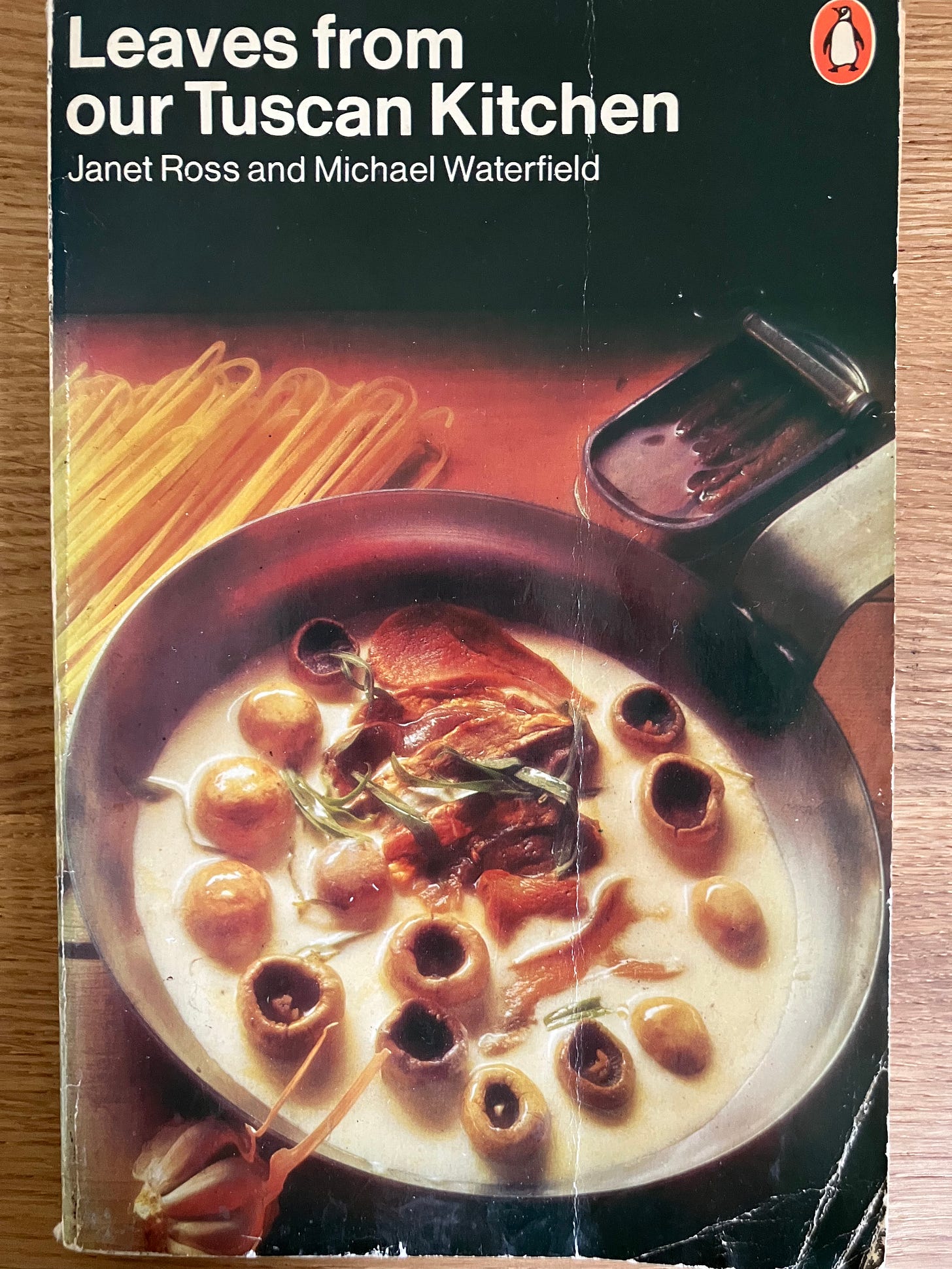

This yellowing paperback has been on my shelf since Penguin Handbooks published it in 1977, the recipes edited and illustrated with line drawings by Michael Waterfield, cook and restaurateur who owned and ran The Wife of Bath at Wye in Kent. I wrote about him back in May and paid subscribers can read this and the other pieces in my archive.

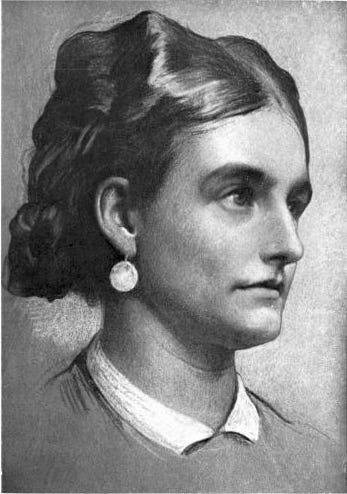

The original book was written by his great-great-aunt, ‘the redoubtable Mrs Ross.’ . Born in 1842 she moved to Tuscany in 1867 and lived there until she died in 1927.

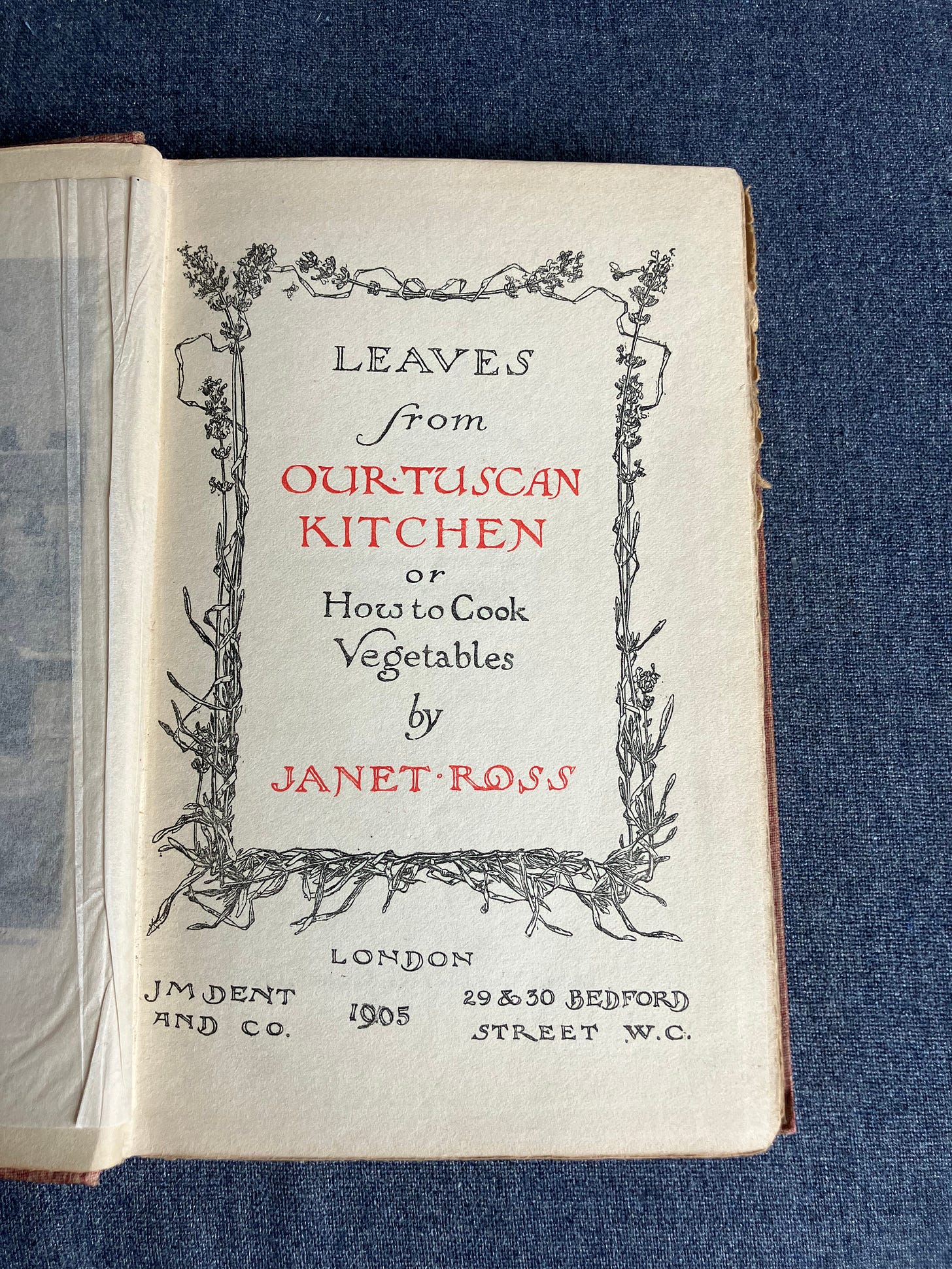

First published in 1899, the eleventh edition was issued in 1936. John Murray published it again in hardback in 1973 and Grub Street in 2006.

Janet would not have cooked herself but treasured a good cook as one of her household servants. She wrote in her introduction …

For years English friends have begged recipes for cooking vegetables in the Italian fashion, so I have written down many of the following from the dictation from our good Giuseppe Volpi, whose portrait, by Mr A.H.Hallam Murray, adorns this little book, and who has been known to our friends for over thirty years.

I must acknowledge, with thanks, the courtesy of Sigri. Fratelli Ingegnoli of Milan, who have permitted me to use and translate what I needed from their excellent little book Come si Cuciano i Legumi.

( Fratelli Ingegnoli were, and still are, seedsmen offering numerous varieties of vegetable seeds)

Janet was born into the aristocratic but impoverished Duff Gordon family and followed her mother and her grandmother in supplementing investment income with work translating and writing books. The family were part of a literary and artistic circle that included William Thackeray George Frederick Watts and George Meredith. A spirited child, she was a fearless rider who enjoyed the freedom of life in the Surrey countryside while her parents took a relaxed approach to her education. A trip to Germany supervised by her German governess equipped her, aged 13, to complete her first translation work. The months spent with her family in Paris enabled her to polish her French and have some informal tutoring from her mother’s friends there. Presented at court to Queen Victoria aged 17, society would now consider her eligible for marriage. Janet seems to have taken an unromantic view of this prospect and, indeed it has been suggested both by her great-great nephew, the historian Anthony Beevor (citing evidence from amongst her papers) and also by Michael Waterfield, that she had lesbian tendencies that she repressed.

In 1860 she married Henry Ross. She was 18 and he was 40. She seems to have been entranced by his horsemanship, his stories of adventures abroad amongst the Kurdish Yezidi people and at at the excavations of Nineveh. He was a partner in an English bank in Alexandria and the allure of financial stability and life in Egypt was clearly irresistible …

Henry makes 5,000 pounds a year and we will live on 1,000 pounds and put by 4,000 - and at the end of five or six years, Click.

Friends and family offered jewellery as wedding gifts but she asked for books to be sent. She relished the opportunities to explore in Egypt and Henry was happy for her to do so. She learned Arabic, rode in the desert, visited the tombs, mixed with influential Egyptian customers of the bank and toured the construction sites of the Suez Canal with Ferdinand de Lesseps .

In 1862 their son Alick was born. They had returned to Surrey for the birth and, as was not unusual, left the baby in the care of a wet nurse and returned to Egypt. Janet and her only child had a rather distant relationship for the rest of their lives. It was in 1866 that the end of the American Civil War saw the price of cotton fall and numerous banks in Egypt were in difficulties. Henry’s bank was collapsing and, in the final tally, although not destitute, they had lost about 70,000 pounds.

Janet sailed to Italy to stay in Florence with her family friend, the British Ambassador en route to Surrey. Back in England they were able to meet up with friends and family, including five year old Alick who was being cared for by his aunt. Florence though was to lure them back and Tuscany was to become their home.

‘Chianti-shire’ has long attracted tourists from northern Europe given its winning combination of climate, landscape, history and art. It was also, crucially, cheaper to live well there than in Britain. Young British noblemen on their Grand Tour in the 1700s would stop by en route from Rome to Naples. By 1910 the British Consul estimated there were 35,000 British subjects living in or around Florence as well as many French, German and Russian emigrés. The Anglo-Florentine community had its own churches, cafés and shops. Published in 1908, E.M.Foster’s A Room With a View conjures the scene. I have also just enjoyed reading Sarah Winman’s novel, Still Life, which covers the period from 1901 to the 1970s and whose characters discover the joys of Italy and Florentine food.

The Rosses initially rented apartments in Florence. In the early days that was the capital of the newly unified Italy but in 1870 King Victor Emmanuel moved his Court and Parliament to Rome. Janet and Henry moved to rent a wing of a country villa at Castagnolo belonging to Lotteringo della Stufa, Court Chamberlain to the King. It is rumoured Janet and ‘Lotti’ were more than ‘close’ but others surmise that Lotti was actually homosexual. She was now 28 and Henry 50 years old. She was busy writing and developing an interest in agriculture, he in collecting orchids. Alick had been living with them for the first time but was then sent back for schooling in England. The local gossips must have loved the drama that unfolded when the romantic novelist Ouida fell in love with Lotti and, when he refused her offer of marriage, exacted revenge on the trio in her novel, Friendship, thinly disguising the family at Castagnolo. Janet kept a copy in the lavatory for guests to read.

Visitors to Castagnolo admired the agricultural improvements and were treated to delicious meals cooked by Giuseppe Volpi. William Gladstone and his wife came, the Duke and Duchess of Teck with other royals as well a writers like Henry James. Janet was the padrona and the system of sharecropping with the contadini known as mezzadria was an ancient one. For 17 years Janet managed and improved the farms and earned the respect of all around her. Her experiences became the basis for pieces she wrote for publication in magazines back in England. It is said that Elizabeth David admired her Italian Sketches for their descriptions of the countryside and for her expertise in the production of wine and olive oil.

Income from her writing helped fund the education of Alick who had graduated from Oxford by 1887. Her biography of her maternal ancestors was success though her history of the Hohenstaufen kings of southern Italy was much less so. Her paintings of Henry’s vast collection of orchids, encouraged by her friend Marianne North, consumed many hours of her time.

Lotti’s failing health forced them to consider buying a home of their own and it was a castle in Settignano with its three farms on the hillside overlooking Florence that was to capture their hearts. Poggio Gherardo was reputedly the setting for Boccaccio’s medieval tales of The Decameron but more prosaically, Janet was able to convince Henry that the farms could be economically viable. This was to be her project and her home for the rest of her life.

She supervised restoration of the castle and the housing for the workers. Her agricultural improvements might have met more resistance had she nor been so willing to work alongside the labourers, demonstrating more modern pruning methods, experimenting with wine production. Over the years they sold surplus fruit and vegetables to market, as well as their wine and a particularly famed vermouth for which she had a secret recipe.

Her relationship with Alick may have been distant but she adopted her 16 year old niece, Lina who remained loyally attached. The castle provide a comfortable retreat for the many guests who would visit on a Sunday afternoon or who were invited to stay in the guest rooms. John Addington Symonds stayed while researching his work on Michelangelo. Now equally famous for his writings about his homosexuality, he enjoyed a close and supportive relationship with Janet. Samuel Clemens who wrote as Mark Twain also had reason to be thankful for her friendship as she helped him and his family find accommodation nearby. The damage from the earthquake of 1895 forced them to sell paintings to raise money for building works and it was the young Bernard Berenson who helped with the valuation. He too became a neighbour and regular visitor from his villa, I Tatti, just down the hill.

Joseph Dent, the publisher visited in 1899 to discuss the books that Lina was writing. Janet saw that a book of her family recipes could be profitable and they did indeed prove to be so.

Janet worked to transcribe and edit Henry’s letters and they were published just before his death in 1902 as Letters from the East 1837-1857. Lina’s marriage to a struggling artist caused a rift between the women at this time of bereavement but trips to revisit Egypt and England did help Janet recover her optimism. By 1906 she was sixty four and had written or edited twelve books.

Virginia Woolf visited one Sunday, knowing little of Janet and wrote …

We had a tremendous tea party one day with Mrs Ross. She was inclined to be fierce, until we explained that we knew you, when she at once knew all about us - our grandparents and aunts and uncles on both sides. She certainly looks remarkable, and had type written manuscripts all scattered about the room. I suppose she writes books …..I imagine she has had a past - but old ladies, when they are distinguished, become so imperious.

She had indeed completed a major scholarly work, The Lives of the Early Medici as told in Their Correspondence, published in 1910. Her books on Pisa and Lucca were in print by 1912 as well as her autobiography, a work so selective it makes no mention of her son. The years of World War l saw a thawing of her relationship with Lina who came to live at Poggio with her two younger children with her husband at the front. At least the produce of the farms meant they had enough to eat and Agostino was cooking for them.

The social unrest following 1918, labour shortages, political unrest and violence inclined Janet, like other liberal minded people, to believe that the Fascisti might offer the hope of solutions, even if they did support female suffrage (which she opposed!). Visitors with letters of introduction still beat a path to her door. The young Kenneth Clark recorded his impressions of his stay there in 1925. Just before her death in 1927 she was working on a guidebook and translating the travel memoirs of a sixteenth century Florentine merchant as well as monitoring the farm accounts.

Asked about how she felt about growing old, she replied …

.. unless I’m ill, I don’t feel any age at all, just the age I have always been.

She was 85. Her ashes were interred in the cemetery in Florence next to her husband.

I am indebted to Sarah Benjamin whose book A Castle in Tuscany gives a full account of the life of this extraordinary, energetic woman.