Elizabeth David died, childless. I have written previously of other women, her contemporaries who worked and wrote to support their children in an era when the bearing ‘illegitimate’ children carried serious social stigma. Patience Gray, Elizabeth Smart and Nancy Spain all found ways to make their way in the world without a husband to provide for their children.

I hope you enjoy my ramblings and reading about cooks and cookbooks….

Subscribe to keep in touch, ideally, become a paid subscriber to read the recipes and get occasional treats - it’s all for a charity too - anthony.nolan.org

Dorothy L. Sayers never wrote a cookbook but is famous for her detective fiction as well as religious writings ( she was a devout Anglican) and her scholarly work translating Dante. An only child, she was raised in a Cambridgeshire Fenland vicarage, excelled at Oxford University and then worked in publishing and teaching before moving to London in 1920. She had written her first two novels before she finally found lucrative employment in 1922 as a copywriter with Bensons, the advertising agency. Recovering from an unsatisfactory relationship with a Russian American writer and poet, she met the father of her child, a car salesman who shared her love of motorcycling. She managed arrangements for the birth and care of her son secretly and none of her friends or family ever knew of his existence. She paid her cousin, Ivy, to include him in her family of foster children and when she visited him she was always referred to as ‘Cousin Dorothy.’

Oswald Fleming ( known as Mac ), the man she married in 1926 , was 12 years older than her and working as a journalist for the News of the World. As a divorced man with a wife still living, it was not in those days permissible for them to have a wedding in church which must have been a considerable disappointment to her family back in the vicarage. A good looking Scot who had been a war correspondent in the Boer War he was still suffering from shell shock and having been gassed in the trenches of France. The early days of their marriage seemed happy. They both loved good food and Mac knew a lot about cooking. She wrote:

I have a first class, experienced male chef, capable of turning out a perfect dinner for any number of people, who not only demands no salary, but also contributes to the support of the household. I came across this paragon some years ago, and, having sampled his cooking and ascertained that he held sound opinions on veal ( which I detest ) and garlic ( which I appreciate ), married him. So far, the arrangement seems to work very well, and since giving me notice would be a troublesome and expensive matter, I am hoping he will stay.

Lord Peter Whimsey, the aristocratic amateur sleuth she created is a gourmet and lover of fine wines. He has survived, albeit traumatised, his wartime experiences. Bunter, who served with him in the trenches, now works as his man servant organising his wardrobe, his wine cellar, preparing meals and also assisting his detection of crimes.

When Harriet Vane eventually marries Lord Peter, it is Bunter who is responsible for transporting the hampers of delicacies, wine and port to their honeymoon house in Busman’s Holiday. The descriptions of food in her books not only serve to set the characters in their social milieu but sometimes are also key to the modus operandi of the killer as in the meal carefully orchestrated by the murderer in Strong Poison.

Mac not only knew about food, he wrote about it. I recently perused this copy of his 1935 Gourmet’s Book of Food and Drink in the British Library and he thanks the editors of the London Evening News and the Sunday Chronicle for permission to quote from his articles they had previously published. He dedicates to book to ‘My wife, who can cook an omelette.’

There are two chapters devoted to the importance of breakfast and a further one solely on suggestions for hangover cures. He insists he preaches moderation but:

Nevertheless, there are times when the unfortunate victim of the night before feels like a warmed-up corpse, and, if there is no inimitable Jeeves on hand to produce the needful restorative, then it behoves Number One to do a spot of looking after himself.

Champagne, mixed with brandy or beaten egg ( the Surgeon Major ) or a concoction of egg, brandy, sugar and frothed milk ( the Doctor ) or the mixture of chilled Bovril and brandy laced with cayenne pepper are all recommended as ‘liveners’ for the afflicted.

The charming illustrations are by Hendy who also illustrated Punch magazine.

As the years went by, the marriage was a lot less happy. Dorothy was busy writing and had been very successful for nine years in her her work at Bensons. She worked on the advertising for Guinness ( Just think what Toucan do ) and The Mustard Club campaign for Coleman’s. His health deteriorated and he was working less, depressed and possibly resentful of his increasingly famous wife. Dorothy was describing him as ‘difficult’ and it seems he was drinking heavily. He no longer cooked.

Mac was eventually persuaded to sign papers and in 1935 little John Anthony was told he had been adopted by ‘Cousin Dorothy’ and ‘Cousin Mac.’ Dorothy paid for his boarding school fees and his expenses at Balliol College, Oxford where he achieved a first class degree. She wrote regularly and met him occasionally but he never visited her home, nor was his existence acknowledged to her family. Her son never sat at her table. A few months before his death at the age of sixty, Anthony Fleming had a conversation with Dorothy’s biographer, Barbara Reynolds and said of his mother, “She did the very best she could.” Mac died suddenly in 1950 and, when Dorothy died in 1957, her son was the sole beneficiary in her will.

But back to Mac’s book….

It is not a cookbook but does offer clear and opinionated advice. It has plenty of advice about fine dining but he also has a chapter extolling the virtues of well cooked tripe and onions ( apparently relished by the then Prince of Wales ), pig’s trotters, black pudding and eel pie.

His chapter on curries would raise many an eyebrow these days but he can make a green salad.

.. this is the best and simplest method of making a plain

French Salad.

Take cos-lettuce for preference because it is usually crisper - as much as is required - wash it well by hand under the tap and put the leaves in a wire straining basket as you wash them - never leave them in water. Now take and shake them up in a napkin to dry up any superfluous moisture, and break them into pieces with the fingers; prepare your chapon, or if preferred rub the inside of the salad bowl, with the cut side of a clove of garlic, add some chopped tarragon, chervil, and chives or endive, if handy, and put your herbs into the bowl. In a tablespoon put a blob of made mustard and a sprinkling of black pepper and salt, fill up the spoon with vinegar and mix thoroughly with a fork, afterwards emptying the contents of the spoon over the salad meat. Then re-fill the spoon, once, twice or thrice, as may be required, with pure Lucca oil and pour into the bowl and mix exceeding well. Vinegar, as you will notice, is used sparingly - fail in this, and your salad is harsh and crude, too much mustard is also a grave mistake……

Always do your salad dressing with a wooden or horn spoon and fork. In France salads are frequently mixed, and served, in a wooden bowl, which may not cut such a dash as a table ornament as some of the glaring cut glass and silver atrocities ( mostly wedding presents ) one frequently sees, but is without doubt the correct utensil. Incidentally, I do not see why we should not be able to obtain beautifully carved wooden salad bowls, plain carved for the modest, with knobs, silver, for the showy, and knobs, gold, unlimited, for the profiteer. En passant, when packing a luncheon hamper, it may be useful to know that a good method of keeping salad meat fresh and crisp is to hollow out a loaf of bread, after cutting a slice off the top to form a lid, and pack the salad inside.

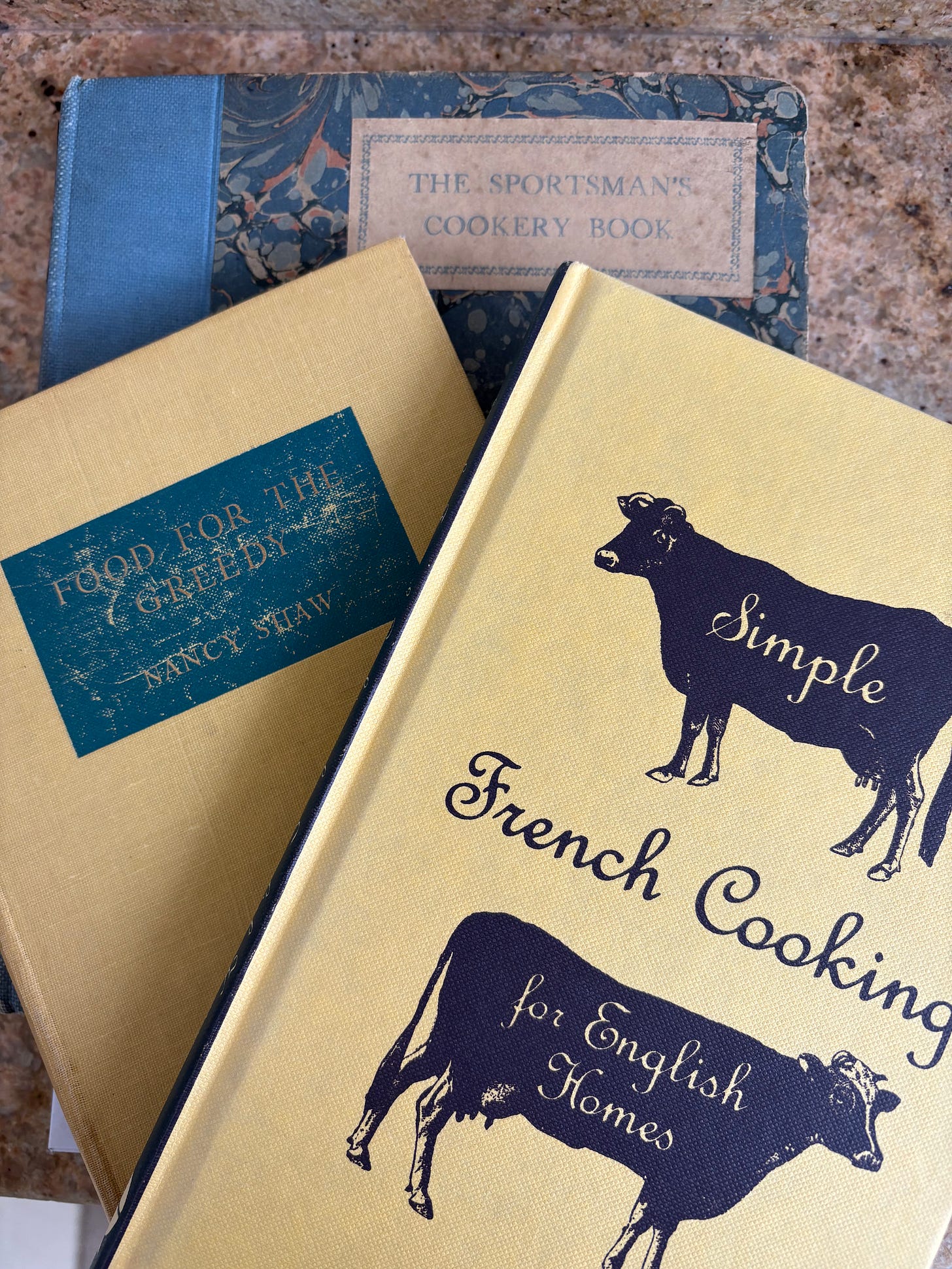

Remember this was written in 1935 or earlier. I regularly read it asserted that, before Elizabeth David’s books inspired cooks of the 1950s, olive oil could only be bought in a chemist shop. A quick look though my bookshelf confirmed that many prewar salads were being dressed with vinaigrette or with olive oil and lemon juice. Even the staunchly traditional Major Pollard in his 1926 The Sportsman’s Cookery Book gives advice on drying and dressing a salad that would prove acceptable today.

In 1922, Lady Jekyll, sister of the gardener, recommends white endive ‘lubricated with oil and vinegar’ as part of a salad course as ‘habitually given now at American luncheon parties.’ I would assume her references to ‘salad oil’ would be understood to mean olive oil.

I read that by 1907 the revised editions of Mrs Beeton’s work included it. John Evelyn the diarist, in 1699, was writing his Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets and using olive oil liberally.

But let the final words lie with the Rev. Sidney Smith and his famous rhyming recipe for salad dressing … albeit he begins with a pounded mixture of boiled potatoes and hard boiled egg yolks passed through a sieve but the sauce is loosened with oil ‘from Lucca.’

Paid subscribers can read the rhyme and the recipe in full and listen to me reading extracts from the foreward to the Gourmet’s Book of Food and Drink.

You need to be a paid subscriber to get the recipe …. so go on, treat yourself!

All income from my subscribers is passed to a charity and in 2025 that is anthony.nolan.org

And if you have read this far, why not click if you liked it and/or leave a comment ? I’d love to hear from you! I will be writing more about some of these women in future posts … and trawling the shelves for more interesting old books.